How GOP megabill fuels debt for future generations

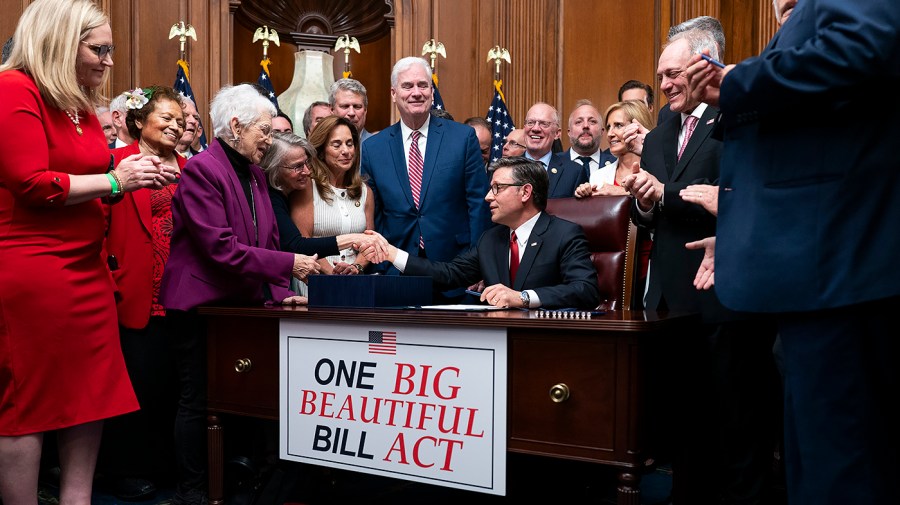

President Trump’s newly passed One Big Beautiful Bill Act will, by most conventional estimates, add trillions to America’s national debt to pay for permanent tax cuts.

Republicans insist the bill will unleash economic activity that offsets any lost tax revenue, but few economists agree. The consequences could be severe for future generations.

A growing debt could make borrowing more expensive in the long term, force policymakers to make painful cuts to spending and social services down the road, slow economic growth and eventually push the nation towards a debt crisis, economists say.

Republicans have historically been among the loudest worriers about the national debt. The House Freedom caucus blasted GOP senators for increasing deficit spending in the final version of the “big, beautiful bill.”

“The Senate isn’t listening—their version adds over $1T to the deficit, completely ignoring the House framework,” wrote Freedom Caucus member Rep. Keith Self (R-Texas) on June 30, before voting for it a few days later.

“This isn’t just reckless—it’s fiscally criminal,” he added.

Self and other fiscal hawks said they received assurances from Trump that helped them come around on the bill. To move the bill through the Senate’s budget reconciliation process, GOP leadership also used a budgetary sleight-of-hand to argue that the bill didn’t balloon deficits, but reduced them.

“Let me be very clear: it reduces the deficit. When you have an honest assessment of what current law is, this is a reduction in deficits over ten years,” White House budget chief Russ Vought asserted on Fox News in the days leading up to the bill’s passage.

The nonpartisan Congressional Budget Office, meanwhile, estimated the bill would add $3.4 trillion to the country’s debt burden over the next decade. The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget estimated $4.1 trillion and the conservative Cato Institute projected $6 trillion.

“This bill will likely turn out to be the single most expensive legislation since the 1960s,” said Jessica Riedl, an economist and fellow at the Manhattan Institute. “It is one of the most irresponsible bills in memory.”

How we got here

The federal government has long spent more than it has earned, forcing it to borrow money by issuing bonds and other securities, which earn reliable interest for investors.

At the end of 2024, the national debt held by individuals, businesses, and other members of the public was about $28.1 billion, or just under 98 percent of the country’s annual gross domestic product (GDP).

That’s different from the commonly quoted gross debt of $36 trillion, which includes intragovernmental debt — money one part of the federal government owes to another part, such as the trust funds that supply Social Security. This gross debt is used to determine when the government is near the national debt limit, a ceiling that has become a political football in recent years.

Economists often prefer to measure the debt held by the public relative to GDP, rather than in absolute terms, because that better describes the country’s ability to keep up with payments.

The debt has grown significantly relative to GDP in the last five years, largely as a result of trillions of dollars in federal relief spending during the COVID-19 pandemic.

The yearly cost of interest on the debt is also substantial, accounting for about 16 percent of total federal spending in the 2025 fiscal year.

Even before the “big, beautiful bill” came into the picture, economists warned long-term spending on that trajectory was unsustainable. The new legislation includes about $4 trillion in tax cuts and new spending, partly offset by $1.1 trillion in net spending reductions.

“There may be a very short-run positive economic effect, but the long-run impact will be much worse,” said Dominik Lett, a policy analyst at the Cato Institute, of the megabill. “We are particularly damning future generations.”

Downstream borrowing effects

As the United States borrows more money, interest rates on government bonds generally rise to incentivize investors to buy more debt. That, in turn, increases the cost of borrowing for everyday forms of consumer and business lending.

Factoring in the impacts of the megabill, the Yale Budget Lab projected that the yield on 10-year Treasury bonds — a key indicator of investor sentiment — would rise an additional 1.2 percentage points by 2054, compared to if the bill didn’t pass.

That would push up costs on mortgages, commercial real estate loans, and other kinds of borrowing, said Ernie Tedeschi, an economist at the lab and a member of former President Biden’s Council of Economic Advisors.

In five years, the interest on a mortgage on a typical house in 2024 — based on a $413,000 loan with a 20 percent down payment — could go up an additional $1,100 every year due to the bill, Tedeschi estimated. In 30 years, the bill would add $4,000 a year to that mortgage’s interest.

“I think that Americans, having gone through periods, first of inflation, higher prices, during the pandemic, and then higher interest rates later on in the pandemic, appreciate that higher interest rates are not a remote concern for them, or something that only affects the financial sector,” he said.

“That’s a kitchen table issue,” he added.

Increased government borrowing could also disincentivize other types of investment, said Ben Harris, an economist at the Brookings Institution.

“You’ll have so many Americans and foreigners, people who would have invested the United States, buying up the debt rather than investing other productive things — everything from technology to health care, everything that really makes us a productive country — that will now be going will be directed towards paying off our our debt,” he said.

The CBO estimated at the beginning of this year that the debt would reach 166 percent of the GDP by 2054. Several estimates say the bill could push that ratio even higher. The Yale Budget Lab projects that the debt-to-GDP ratio in 2054 will be 179.1 percent when factoring in the megabill.

Some Democrats and Republicans have called to eliminate the country’s debt ceiling entirely, arguing that the laws of economic gravity don’t apply to U.S. debt given the scale and resiliency of American commerce. Economists aren’t so sure, given the rate at which the debt is outpacing the growth of the economy.

“Long-term, we risk a full debt crisis,” Riedl said. “At some point, the bond market will not be able to supply that much lending at plausible interest rates. A debt crisis would likely begin with the bond market panicking over the government’s borrowing demands, which can hurt the market and drastically raise interest rates until Washington commits to drastic deficit reduction.”

Tough choices ahead

Some budget hawks have dreamed of a balanced budget, where Washington would spend only as much as it earns in a fiscal year. However, that would require massive cuts to spending or significant tax hikes, both of which would be politically perilous.

Several economists estimated that stabilizing the debt with respect to GDP would take at least $10 trillion in deficit reduction over the next ten years — “a tall order,” Tedeschi said.

“To put that in perspective, the most controversial cuts to Medicaid [in the megabill], that even Republicans in Congress were debating and not all of them were comfortable with, never got higher than $900 billion in a decade,” he said.

Among the biggest single line items driving the debt are Social Security and Medicare, the federal health insurance program for seniors. Debt hawks have long looked to cutting those programs as a way to reduce deficits.

“Closing these deficits could require doubling middle class taxes or essentially eviscerating Social Security, Medicare and defense,” Riedl said.

Social Security and Medicare are both marching toward insolvency on current trajectories, with estimates that funds will start running short within the next decade. The megabill slightly accelerates this timeline, according to an estimate by the Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget.

That could force Congress to make tough decisions about raising taxes or cutting benefits as soon as 2032.

“If we have more taxes to close larger Social Security and Medicare shortfalls, those will likely be done through the payroll tax,” said Robert Greenstein, a visiting fellow at the Brookings Institution. “Almost certainly part of the gap will be filled by Social Security benefit cuts, which would now be somewhat larger than they otherwise would be. And those cuts would affect people in future generations.”

The megabill does reduce taxes for some Americans, particularly those high on the income scale. But it is still likely to decrease GDP in the long run compared to baseline policy assumptions: 0.3 percent less in 10 years and 4.6 percent in 30 years, according to analysis from the University of Pennsylvania’s Wharton School.

“The more we borrow now, the harder those decisions will be in the future,” added Lett. “So if people think the changes in the bill are already draconian, it will make the future changes necessary even worse.”